CONTEXT

Floyd Collins. Photo courtesy of Hidden River Cave.

THE REAL FLOYD COLLINS

Floyd was born in Kentucky in 1887 to Lee Collins and Martha Jane Burnett and was the third of eight children. His younger sister Nellie and younger brother Homer are also characters in the musical. Their mother, Martha, died in 1915 and their father married Sarilda Jane Buckingham, known as “Miss Jane.”

The Collins family were farmers, but even from a young age, Floyd was interested in caves - and there were plenty of caves for him to explore. Floyd grew up in what is now part of the Mammoth Cave National Park. When he was a boy, he would go down into the caves and bring back souvenirs - prehistoric artifacts like spearpoints and arrowheads or pieces of stalactites and stalagmites - to sell to tourists.

Floyd spent most of his time exploring the caves near his farmstead – it was his passion. In 1917, he even found a cave opening on his family’s property that he called Crystal Cave. His whole family pitched in to help make it ready for tourists, creating pathways and a larger entrance. Unfortunately, Crystal Cave was far from the main road and didn’t attract many visitors. Floyd continued exploring in hopes of finding even more extraordinary caves that would be more accessible for tourists.

On January 30th, 1925, while Floyd was exploring a new cave opening, his leg got pinned down by a large rock; he was trapped. That historical moment is the point of departure for the musical FLOYD COLLINS.

Photo Cour

THE REAL STEPHEN BISHOP

Clyde Voce, the actor who plays ED BISHOP

A print engraving of STEPHEN BISHOP

100 YEARS AGO

The musical FLOYD COLLINS is set in Cave City, Kentucky in 1925. Scroll through the images below to see what life was like in that region 100 years ago.

MAMMOTH CAVE NATIONAL PARK

Floyd Collins lived in what is now part of the Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky. It became a national park in 1941, sixteen years after Floyd died.

However, evidence shows that prehistoric people had been coming to these caves as early as 5,000 years ago. Artifacts such as bowls, shells, woven sandals, and cave art that were created by indigenous peoples have been found in the caves.

Today, the Mammoth Cave National Park is the longest known cave system in the world, encompassing about 53,000 acres and 426 miles of passages. People still come to visit the caves and walk around the park.

KENTUCKY CAVE WARS:

A WAR FOR TOURIST DOLLARS

Even before it became a national park, visitors would come to see the Mammoth Caves. The first official tour of the caves took place in 1816. During Floyd Collins’ lifetime, many farmers in the area looked for cave openings on their land so that they could charge tourists to visit. During the “Kentucky Cave Wars,” more than twenty different privately owned caves tried to compete for tourist dollars. In this clip, Ranger Shannon Hurley from Mammoth Cave National Park describes these Cave Wars.

THE STORY GETS OUT

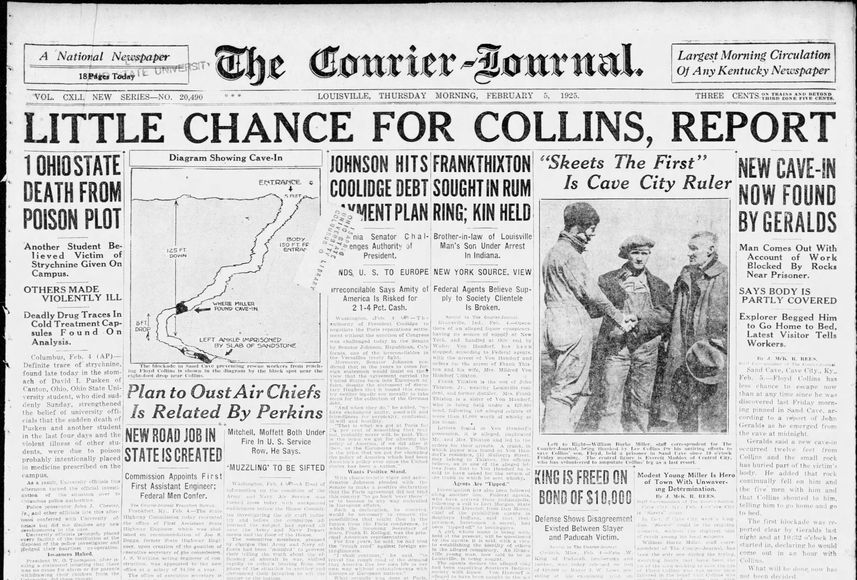

Local correspondents in Cave City, KY let the larger Louisville papers know that a man was trapped in Sand Cave. William “Skeets” Miller, a twenty-one-year-old writer from the Louisville Courier-Journal, was one of the first journalists to report on Floyd’s story. His nickname, “Skeets,” played on his small size, comparing him to a mosquito. Because Skeets was so small, he was able to crawl into the cave and get close enough to Floyd to interview him. The interviews humanized Floyd and created a huge amount of sympathy for him. Skeets became intertwined with the story; he joined the rescue attempt and almost succeeded in freeing Floyd. Skeets won the Pulitzer Prize in Reporting in 1926 for his articles about Floyd.

William "Skeets" Miller. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

MEDIA FRENZY

What started as a local Kentucky story quickly became a major national sensation, making it one of the earliest examples of a media frenzy. Skeets wasn’t the only reporter on the scene; in fact, about 150 members of the media - journalists, photographers, sketch artists, radio operators - came to the site. Not all of the reporting was accurate, and misinformation was spread. Some newspaper articles said Floyd had been freed when he hadn’t been. Others got facts wrong about how he had become trapped, how he was positioned in the cave, and his age. Some stories were completely made up, like the story of Alma Clark, who, the newspapers claimed, was Floyd’s fiancée tearfully waiting for his return. Alma Clark was a real person, but she was not in a relationship with Floyd.

What started as a local Kentucky story quickly became a major national sensation, making it one of the earliest examples of a media frenzy. Skeets wasn’t the only reporter on the scene; in fact, about 150 members of the media - journalists, photographers, sketch artists, radio operators - came to the site. Not all of the reporting was accurate, and misinformation was spread. Some newspaper articles said Floyd had been freed when he hadn’t been. Others got facts wrong about how he had become trapped, how he was positioned in the cave, and his age. Some stories were completely made up, like the story of Alma Clark, who, the newspapers claimed, was Floyd’s fiancée tearfully waiting for his return. Alma Clark was a real person, but she was not in a relationship with Floyd.

Film footage of the rescue attempt

The nation was hooked. Newspapers sold out and needed to be reprinted to sell more copies. Radio announcers gave frequent updates on Floyd’s situation. The public was so concerned that they flooded radio stations and newspapers with phone calls asking for more information. Motion picture crews were on site and filmed the rescue attempt. Millions of people watched the footage in movie theaters. Prayers and vigils were held. The entire country was captivated, including President Coolidge, who reportedly asked for daily briefings from the National Guardsmen trying to free Floyd. Even members of Congress left sessions to get updates on Floyd’s situation.

Film footage of the rescue attempt

Film footage of the rescue attempt

CARNIVAL SUNDAY

Carnival Sunday. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

Because of the media attention, crowds began to gather at the cave entrance. The nearby town of Cave City had a population of 680 people in 1925. On February 8th - “Carnival Sunday” - an estimated 10,000–50,000 people came to the area. The two restaurants in town ran out of food. Rooming houses were full. Stalls popped up selling over-priced hamburgers and sandwiches. Souvenirs were sold. There were jugglers entertaining the crowd and church services held with sermons about Floyd.